“Creativity is not a talent. It is a way of operating.” – John Cleese (1991)

During my training and coaching of agile teams, I come across a great many individuals who label themselves far too easily with the words “I’m not creative at all”. I firmly agree with John Cleese in his quote here, that creativity isn’t a personal attribute as such, it’s more an environment and a process of de-filtering our ideas.

Why do we need to be creative in a scrum team?

Creativity is an essential ingredient for attempting to navigate the world of complex problems. I think the first step for scrum teams and facilitators is to determine whether the problems we are working on are complex in nature. A complex problem is one where there are large degrees of uncertainty in the domain and indeed the solution, therefore prior expertise is not necessarily going to help us solve it – indeed our prior experience may well blinker our potential solutions.

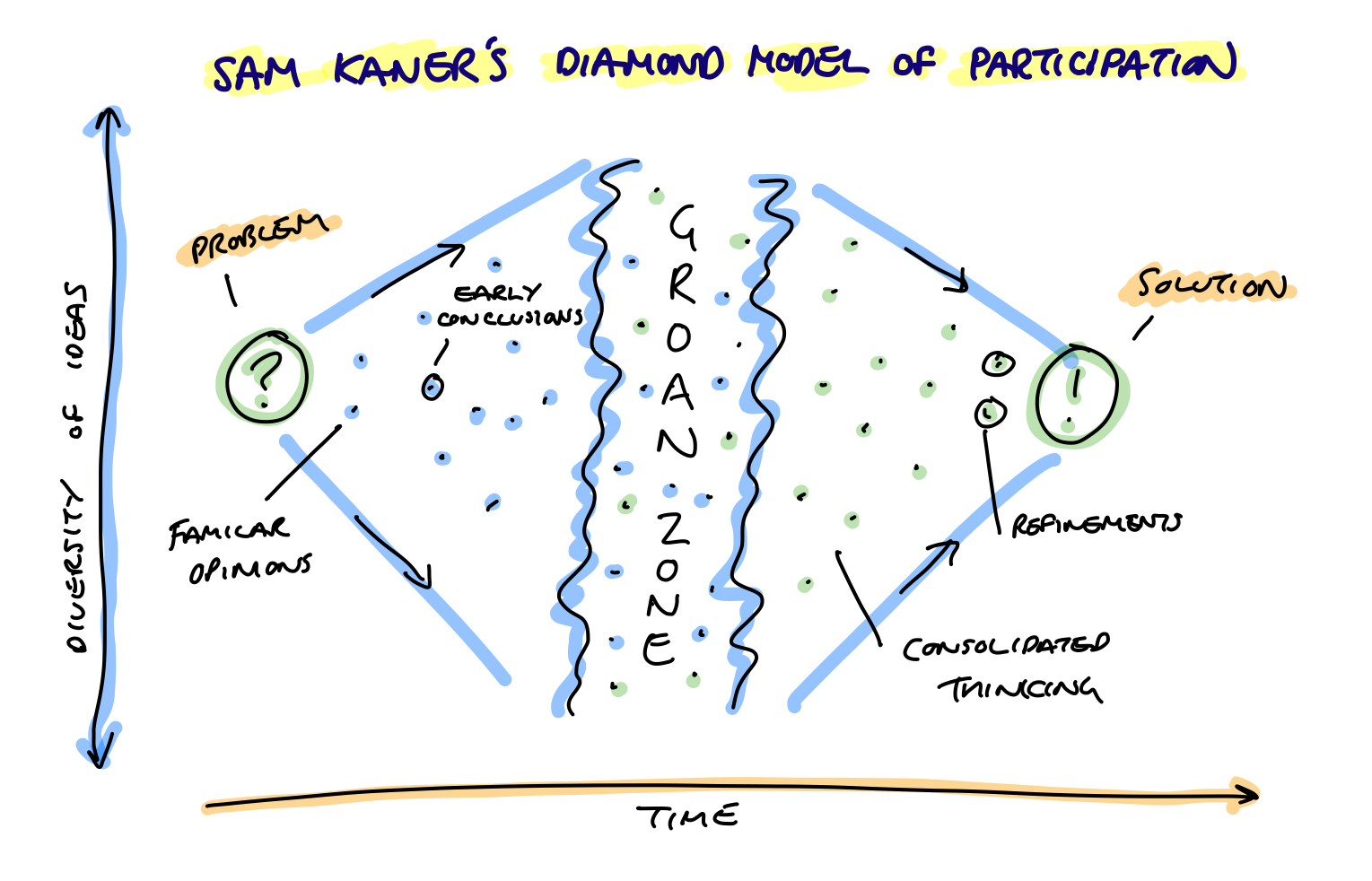

I hold Sam Kaner’s book on facilitating decision-making in high regard on this subject, as a common anti-pattern I see in the scrum teams and scrum masters I coach, is a tendency to jump onto early suggestions too easily, usually as an attempt to stay away from the uncomfortably awkward “Groan Zone”.

The first step as a facilitator is purely to acknowledge Kaner’s model here, and be content to move past the obvious and familiar options, and into the “groan zone” itself. The “Groan Zone” is named due to the audible disharmony a facilitator can expect to hear as the participants start asking themselves “Will we ever make a decision here? How will we find a way forward?”. This is the point to start eliminating some ideas and narrowing towards a more viable set of options. The groans will start to diminish and bring a sense of focus back to proceedings to help the team agree a way forward.

A sense of safety and spontaneity are both fundamental building blocks to a team accessing this kind of creative journey, by removing the personal responsibility we feel for coming up with our own ideas that are original, feasible and socially acceptable to our colleagues and forging an interest in exploring new and alternative ideas to explore.

In this post, I will share five different approaches to help you and your team diversify your thinking around the complex problems you may be trying to solve.

1: Get Past The Obvious

1: Get Past The ObviousIn order to fully explore a more creative space, allow your team members to download the mind of the logical and familiar ideas first. This can be a simple post-it based exercise to write as many ideas down at the outset of the session in pairs, and you will notice as the rate of new ideas starts to slow, that tends to be where the more “ingenious” ideas start to emerge.

2: Form Random Connections

2: Form Random ConnectionsAs the ideas begin to slow, the creative mind can be sparked back into life by introducing a random element to the process. Using the “rubber duck” image as an example – you could ask the team to write down words they associate with the image (such as “yellow”, “toy”, “duck”, “rubber”) and then use those words to form a link to new ideas. Sometimes the creative process begins from forming simple connections faster, and that may lead to new and interesting alternatives.

3: Invert The Problem

3: Invert The ProblemForcing the brain into solution-mode from the outset can be a slow and sometimes frustrating process – which can lead some people to give up too soon. Asking the team “What would make this problem worse?” seems to be counter-productive, but it is often easy for the problem-focussed mind to examine and amplify the problem. Sometimes simply “flipping” how the problem could be made worse, may actually be a way to make the problem better. As an example, if my problem was a headache, it could be made worse by playing loud music into my ears. On the flip side – maybe I should reduce the volume of my speakers or try moving to a quieter room for a while??

Sometimes “we” might be the barrier to our own creativity and solutions. How might our own preconceptions be excluding other options? We can adjust that deliberately by presenting different personas and characters to the scenario and asking how those people might deal with the situation. This helps relieve some of the personal opinions and assumptions from the scenario – and introduces a new, perhaps unconsidered perspective. These external perspectives do not have to be limited to the team or the domain – some of the most fun creative meetings I have facilitated have asked questions such as “How might Homer Simpson solve this problem?” or “How might my six year old daughter tackle this problem? – sometimes a simpler solution is available and we haven’t been looking for it through the right lens.

5: Increase Safety

5: Increase SafetyPersonally I think this is possibly the hardest, yet most essential part. The “open mode” described by John Cleese in his 1991 talk about creativity is built on the premise of safety. Creativity emerges from a playful state – where participants feel less pressure, a slower pace, and less focus on winning and losing. As a facilitator, our role is to create that kind of playful space for a creative session- like Sprint Planning or Sprint Retrospectives. Sometimes safety can be increased by what we say, but mostly I think it’s about an environment we create – even online. Reminding people that we value the quantity of ideas over the quality of them, setting working agreements to ensure ideas aren’t judged by other team members, will all help. But perhaps most importantly, team safety comes from feeling safe to fail – acknowledging that we are not perfect enough to have the perfect idea yet – almost giving your team explicit permission to have a “less than perfect idea”.